Watch this visit (see the youtube link) to Maroon Town in Jamaica and listen to them tell their own story. You can then press the back button to come back to this page.

wikipedia describes the Igbo as follows

Igbo people in Jamaica were shipped by Europeans onto the island between the 18th and 19th century as forced labour on plantations. Igbo people constituted a large portion of the African population in slave-importing Jamaica. Some slave censuses detailed the large number of Igbo slaves on various plantations throughout the island on different dates throughout the 18th century.[2] Their presence was a large part in forming Jamaican culture as their cultural influence remains in language, dance, music, folklore, cuisine, religion and mannerisms. Many words in Jamaican Patois have been traced to the Igbo language. In Jamaica the Igbo were referred to as either Eboe, or Ibo.[3] However, the majority of African words in Jamaican Patois is from the Asante-Twidialect of the Akan language of Ghana, as Igbo mostly populated the northwestern section of the island.[4]

Contents

History

Originating primarily from what was known as the Bight of Biafra on the West African coast, Igbo people were taken in relatively high numbers to Jamaica as slaves, beginning around 1750. The primary ports from which the majority of these enslaved people were taken from were Bonny and Calabar, two port towns that are now in south-eastern Nigeria.[5] The slave ships arriving from Bristol and Liverpool delivered the slaves to British colonies including Jamaica. The bulk of Igbo slaves arrived relatively late, between 1790 and 1807.[6] Jamaica, after Virginia, was the second most common disembarkation point for slave ships arriving from the Bight of Biafra.[7]

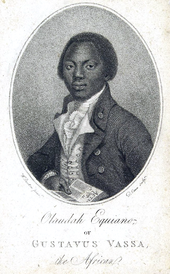

Igbo people were spread on plantations on the island’s northwestern side, specifically the areas around Montego Bay and St. Ann’s Bay, and[8]consequently, their influence was concentrated there. The region also witnessed a number of revolts that were attributed to people of Igbo origin. Slave owner Matthew Lewis spent time in Jamaica between 1815 and 1817 and studied the way his slaves organised themselves by ethnicity and he noted, for example, that at one time when he “went down to the negro-houses to hear the whole body of Eboes lodge a complaint against one of the book-keepers”.[9]Olaudah Equiano, a prominent member of the movement for the abolition of the slave trade, was an African-born Igbo ex-slave. On one of his journeys to the Americas as a free man, as documented in his 1789 journal, Olaudah Equiano was hired by a Dr. Charles Irving to recruit slaves for his 1776 Mosquito Shore scheme in Jamaica, for which Equiano hired Igbo slaves, whom he called “My own countrymen”. Equiano was especially useful to Irving for his knowledge of the Igbo language, using Equiano as a tool to maintain social order among his Igbo slaves in Jamaica.[10]

Igbo slaves were known, many a times, to have resorted to resistance rather than revolt and maintained “unwritten rules of the plantation” of which the plantation owners were forced to abide by.[11] Igbo culture influenced Jamaican spirituality with the introduction of Obeah folk magic; accounts of “Eboe” slaves being “obeahed” by each other have been documented by plantation owners.[9] However, it is more likely that the word “Obeah” was also used by Akan slaves, before Igbos arrived in Jamaica.[12] Other Igbo cultural influences are the Jonkonnu festivals, Igbo words such as “unu” “una”, idioms, and proverbs in Jamaican patois. In Maroon music were songs derived from specific African ethnic groups, among these were songs called “Ibo” that had a distinct style.[13]

Igbo slaves were known to have committed mass suicides, not only for rebellion, but in the belief their spirits will return to their motherland.[5][14] In a publication of a 1791 issue of Massachusetts Magazine, an anti-slavery poem was published called Monimba, which depicted a fictional pregnant Igbo slave who committed suicide on a slave ship bound for Jamaica. The poem is an example of the stereotype of Igbo slaves in the Americas.[15][16] Igbo slaves were also distinguished physically by a prevalence of “yellowish” skin tones prompting the colloquialisms “red eboe” used to describe people with light skin tones and African features.[17] Igbo people were hardly reported to have been maroons, although Igbo women were paired with Coromantee(Akan) men so as to subdue the latter due to the idea that Igbo women were bound to their first-born sons’ birthplace. [18]

Archibald Monteith, born Aneaso, was an Igbo slave taken to Jamaica after being tricked by an African slave trader. Anaeso wrote a journal about his life, from when he was kidnapped from Igboland to when he became a Christian convert.[19]

After the slavery era, Igbo people also arrived on the island as indentured servants between the years of 1840 and 1864 along with a majority Congo and “Nago” (Yoruba) servants.[20] Since the 19th century most of the citizens of Jamaica of African descent have assimilated into the wider Jamaican society and have largely dropped ethnic associations with Africa.

Rebellions

Igbo slaves, along with “Angolas” and “Congoes” were most prone to be runaways. In slave runaway advertisements held in Jamaica workhouses in 1803, out of 1046 Africans, 284 were described as “Eboes and Mocoes”, 185 “Congoes”, 259 “Angolas”, 101 “Mandingoes”, 70 Coromantees, 60 “Chamba” of Sierra Leone, 57 “Nagoes and Pawpaws”, and 30 “scattering”. 187 were “unclassified” and 488 were “American born negroes and mulattoes”.[21]

Some popular slave rebellions involving Igbo people include:

- The 1815 Igbo conspiracy in Jamaica’s Saint Elizabeth Parish, which involved around 250 Igbo slaves,[22] described as one of the revolts that contributed to a climate for abolition.[23] A letter by the Governor of Manchester to Bathurst on April 13, 1816,[24]quoted the leaders of the rebellion on trial as saying “that ‘he had all the Eboes in his hand’, meaning to insinuate that all the Negroes from that Country were under his controul”.[25] The plot was thwarted and several slaves were executed.

- The 1816 Black River rebellion plot, was according to Lewis (1834:227—28), carried out by only people of “Eboe” origin.[26] This plot was uncovered on March 22, 1816, by a novelist and absentee planter named Matthew Gregory “Monk” Lewis. Lewis recorded what Hayward (1985) called a proto-Calypso revolutionary hymn, sung by a group of Igbo slaves, led by the “King of the Eboes”. They sang:

- “Mr. Wilberforce” was in reference to William Wilberforce a British politician, who was a leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. “Buckra” was a term introduced by Igbo and Efikslaves in Jamaica to refer to white slave masters.[28]

Culture

Among Igbo cultural items in Jamaica were the Eboe, or Ibo drums popular throughout all of Jamaican music.[29] Food was also influenced, for example the Igbo word “mba” meaning “yam root” was used to describe a type of yam in Jamaica called “himba”.[30][31] Igbo and Akan slaves affected drinking culture among the black population in Jamaica, using alcohol in ritual and libation. In Igboland as well as on the Gold Coast, palm wine was used on these occasions and had to be substituted by rum in Jamaica because of the absence of palm wine.[32]Jonkonnu, a parade that is held in many West Indian nations, has been attributed to the Njoku Ji “yam-spirit cult”, Okonko and Ekpe of the Igbo. Several masquerades of the Kalabari and Igbo have similar appearance to those of Jonkonnu masquerades.[33]

Language

Much of Jamaican mannerisms and gestures themselves have a wider African origin, rather than specific Igbo origin. Some examples are non-verbal actions such as “sucking-teeth” known in Igbo as “ima osu” or “imu oso” and “cutting-eye” known in Igbo as “iro anya”, and other non-verbal communications by eye movements.[34]

There are a few Igbo words in Jamaican Patois that resulted when slaves were restricted from speaking their own languages. These Igbo words still exist in Jamaican vernacular, including words such as “unu” meaning “you (plural)”,[17] “di” meaning “to be (in state of)”, which became “de”, and “Okwuru” “Okra” a vegetable.[35]

Some words of Igbo origin are “akara”, from “àkàrà”, type of food, also from Ewe and Yoruba;[36]“attoo”, from “átú” meaning “chewing stick”.[37] Idiom such as, via Gullah “big eye”, from Igbo “anya ukwu” meaning “greedy”;[38][39][40]“breechee”, from “mbùríchì”, an Nri-Igbo nobleman;[41]“de”, from “dị” [with adverbial] “is” (to be);[42][43] “obeah“, from “ọbiạ” meaning “doctoring””mysticism”;[44]“okra“, from “ọkwurụ”, a vegetable;[35][44]“poto-poto”, from “opoto-opoto”, “mkpọtọ-mkpọtọ” meaning “mud””muddy”, also from Akan;[35]“Ibo”,”Eboe”, from “Ị̀gbò”, [45] “se”, from “sị”, “quote follows”, also from Akan “se” and English “say”;[46]“soso”, from sọsọ “only”;[35][47]“unu”,”una”, from “únù”, “you (plural)”.[48]

Proverbs

“Ilu” in Igbo means proverbs,[49] a part of language that is very important to the Igbo. Igbo proverbs crossed the Atlantic along with the masses of enslaved Igbo people. Several translated Igbo proverbs survive in Jamaica today because of the Igbo ancestors. Some of these include:

- Igbo: “He who will swallow udala seeds must consider the size of his anus”

- Jamaican: “Cow must know ‘ow ‘im bottom stay before ‘im swallow abbe [Twi ‘palm nut’] seed”; “Jonkro must know what ‘im a do before ‘im swallow abbe seed.”

- Igbo: “Where are the young suckers that will grow when the old banana tree dies?”

- Jamaican “When plantain wan’ dead, it shoot [sends out new suckers].”

- Igbo: “A man who makes trouble for other is also making one for himself.”

- Jamaican: “When you dig a hole/ditch for one, dig two.”

- Igbo: “The fly who has no one to advise it follows the corpse into the ground.”

- Jamaican: “Sweet-mout’ fly follow coffin go a hole”; “Idle donkey follow cane-bump [the cart with cane cuttings] go a [animal] pound”; “Idle donkey follow crap-crap [food scraps] till dem go a pound [waste dump].”

- Igbo: “The sleep that lasts for one market day to another has become death.”

- Jamaican: “Take sleep mark death [Sleep is foreshadowing of death].”

Religion

“Obeah” refers to folk magic and sorcery that was derived from West African sources. The W. E. B. Du Bois Institute database[12] supports obeah being traced to the “dibia” or “obia” meaning “doctoring”[9] traditions of the Igbo people.[50][51] Specialists in “Obia” (also spelled Obea) were known as “Dibia” (doctor, psychic) practiced similarly as the obeah men and women of the Caribbean, like predicting the future and manufacturing charms.[52][53] In Jamaican mythology, “River Mumma”, a mermaid, is linked to “Oya” of the Yoruba and “Uhamiri/Idemili” of the Igbo.[54]

Among Igbo beliefs in Jamaica was the idea of Africans being able to fly back home to Africa.[55]There were reports by Europeans who visited and lived in Jamaica that Igbo slaves believed they would return to their country after death.[56]

Notable Jamaicans of Igbo descent

- Archibald Monteith, an ex-slave who was called “Aneaso” born in Africa, and brought to Jamaica and later wrote an autobiography[19]

- One of Malcolm Gladwell‘s European ancestors had a child by an Igbo slave, which started off the mixed-race Ford family on Gladwell’s mothers side.[57]

In the case of Nigeria, we know that it was from the East that Jamaicans came. This was in the latter part of the 18th century, especially as the English slave trade came to an end in 1807. This is also the period in which there was a huge inflow of persons from the Congo-Angola area.

This spike in the slave trade in the early 19th century was connected to the development of the coffee industry in Jamaica, following the collapse of coffee in Haiti after the revolution. This occurred mainly in the Dallas mountain overlooking UWI, in Upper Clarendon where my family is from and in the hills of northern Manchester – towards Coleyville and Wait-a Bit in Upper Trelawny.

Eastern Nigeria is classic yam country, especially for white yam (Dioscorea rotundata). Yams festivals are an integral part of their culture, as it is in other parts of Nigeria and Ghana. I speculate that the concentration of yam cultivation in the Trelawny hills, and our own yam festival there, may have to do with this massive Eastern Nigerian inflow at the end of the slave trade. But again, much more research is needed before one can confidently make such an assertion.

It is not possible to declare that the Eastern Nigerian influence in Jamaica – apparent in expressions such as ‘red ibo’ – is Igbo. True, nearly all the Nigerian movies we love to watch in Jamaica are of Igbo origin. Village scenes filled with the assertive females reminds us of rural Jamaica. Most of the well-known Nigerian movie stars, such as Patience Ozokwor, Richard Mofe-Damijo and Emeke Ike, are Igbo.

Undoubtedly, there is a major Igbo influence on Jamaican culture. But Eastern Nigeria is a huge area with many different ethnic groups. Igbo from Aro were deeply involved in the slave trade. But so were Ijaws from the Delta and the Ibibios further east. Indeed, the real centre of the Eastern Nigerian slave trade at the end of 18th century was in the Efik (Ibibio) areas around Creek Town and Duke Town, on the Cross river near the Cameroon border. Again, most enslaved people came from inland rather than from the coast, and would probably have been from weaker Igbo and Ibibi

http://old.jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20080113/focus/focus4.html

Watch this The tribe of Benjamin Judah and Levi https://youtu.be/Dym6ccCgTus

The 12 tribes of Judah debunked https://youtu.be/-JTQbDOt9AU

And Igbo in Africa (tribe of Gad) https://youtu.be/Vnm9YZt7AuM

Igbo people in the Atlantic slave trade

The Igbo in the Atlantic slave trade became one of the main ethnic groups enslaved in the era lasting between the 16th and late 19th century. Located near indigenous Igbo territory, the Bight of Biafra (also known as the Bight of Bonny),[1] became the principal area in obtaining Igbo slaves.[2] The Bights major slave trading ports were located in Bonny and Calabar; a large number of these slaves Igbo.[3][4] Slaves, kidnapped or bought from fellow Igbos, were taken to Europe and the Americas by European slave traders.[5] An estimated 14.6% of slaves were taken from the Bight of Biafra between 1650 and 1900, the third greatest percentage in the era of the transatlantic slave trade.[6]

Ethnic groups were fairly saturated in certain parts of the Americas because of planters preferences in certain African peoples.[7] The Igbo were dispersed to colonies such as Jamaica,[8]Cuba,[8] Haiti,[8] Barbados,[9] United States,[10] Belize,[11] Trinidad and Tobago[12] among others. Elements of Igbo culture can still be found in these places. In the United States the Igbo were found common in the state of Maryland and Virginia.[13]

Contents

Effects

Dispersal

Some recorded populations of people of African descent on Caribbean islands recorded 2,863 Igbo on Trinidad and Tobago in an 1813 census;[16] 894 in Saint Lucia in an 1815 census;[17] 440 on Saint Kitts and Nevis in an 1817 census;[18] and 111 in Guayana in an 1819 census.[19][N 1]

Barbados

The Igbo were dispersed to Barbados in large numbers. Olaudah Equiano, a famous Igbo author, abolitionist and ex-slave, was dropped off there after being kidnapped from his hometown near the Bight of Biafra. After arriving in Barbados he was promptly shipped toVirginia.[20] At his time, 44 percent of the 90,000 Africansdisembarking on the island (between 1751 and 1775) were from thebight. These Africans were therefore mainly of Igbo origin. The links between Barbados and the Bight of Biafra had begun in the mid-seventeenth century, with half of the African captives arriving on the island originating from there.[21]

Haiti

Some slaves arriving in Haiti included Igbo people who were considered suicidal and therefore unwanted by plantation owners. According to Adiele Afigbothere is still the Creole saying of Ibos pend’cor’a yo (the Ibo hang themselves).[22] Aspects of Haitian culture that exhibit this can be seen in the Ibo loa, a Haitian loa (or deity) created by the Igbo in the Vodun religion.[8]

Jamaica

Bonny and Calabar emerged as major embarkation points of enslaved West Africans destined for Jamaica’s slave markets in the 18th century.[23] Dominated by Bristol and Liverpool slave ships, these ports were used primarily for the supply of slaves to British colonies in the Americas. In Jamaica, the bulk of Igbo slaves arrived relatively later than the rest of other arrivals of Africans on the Island in the period after the 1750s. There was a general rise in the amount of enslaved people arriving to the Americas, particularly British Colonies, from the Bight of Biafra in the 18th century; the heaviest of these forced migrations occurred between 1790 and 1807.[24] The result of such slaving patterns made Jamaica, after Virginia, the second most common destination for slaves arriving from the Bight of Biafra; as the Igbo formed the majority from the bight, they became largely represented in Jamaica in the 18th and 19th century.[25]

United States

In the United States the Igbo slaves were known for being rebellious. In some states such asGeorgia, the Igbo had a high suicide rate.[26][27][28] Igbo slaves were most numerous in the states of Maryland and Virginia,[29]

In the 19th century the state of Virginia received around 37,000 slaves from Calabar of which 30,000 were Igbo according to Douglas B. Chambers.[29] The Frontier Culture Museum of Virginiaestimates around 38% of captives taken to Virginia were from the Bight of Biafra.[30] Igbo peoples constituted the majority of enslaved Africans in Maryland.[29] Chambers has been quoted saying “My research suggests that perhaps 60 percent of black Americans have at least one Igbo ancestor…”[31]

An American Maroon extract below. He speaks of the Sabbath a Hebrew and Jewish Holy day when he was captured. He is of African heritage but may not be of Igbo descent. However statistics show he probably had an Igbo ancestor.

CHAPTER III.

http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/iwilliams/iwilliams.html

We were captured on a quiet Sabbath morning, about ten o’clock, when the sun was smiling brightly, and leaves were rustling with their forest music. While the good people of the land were on their way to God’s house to pray for all mankind, here were two poor wayfarers shot down deliberately, by permission of the laws of this very land. Our captors tied our hands so tight with hitching straps, that we were fain to cry out in our great agony, but knowing it would be of no avail, and only gratify the malice of our captors we bore it all in silence. They had a large wagon close by, and in this we were driven to King George county jail. Before reaching there my wrists swelled up so that they covered the hitching strap that I was tied with, and I asked Mullen to loosen it a little so as to relieve my misery. He refused with oaths, saying, “You shall never get away from us; we wont give you a chance,” and they struck me repeatedly in the face and kicked each of us. On reaching the jail the sheriff, whose name was Dr. Hunter, came up and looked at us. I then had twenty-nine shot in my right arm and forty in my right leg. The doctor counted the holes in the flesh and said as he gazed at the mangled members, “If they were my niggers I would rather have them shot dead than wounded this way.” He abused them roundly for their bad usage of us, not perhaps so much on the grounds of humanity, as because we had depreciated in value, being not so marketable, and the doctor hated to see good property destroyed. Mullen, Bryant and White dared say nothing in reply to him, for he was rich and they were poor, but they cringed and fawned around him like the curs they were. The doctor then had us removed to a comfortable place, and dressed our wounds himself; he was a skillful man, and soon

had us on our feet again. We were put in the dungeon or cell where men condemned to be hung were kept, not a very cheerful place to be sure, but I could not help wishing I should meet that fate rather than be a slave again. I thought of the many sad, desperate men this cell had held, and wondered what their inmost secret feelings were with death staring them in the face, and life’s moments ebbing swiftly away.

Doctor James, the slave dealer who had bought me from Ayler, was at this time away, further south in Georgia, with a large gang of slaves he had taken there to sell. Knowing this fact the sheriff telegraphed to James’ partner in Richmond, and he came on at once, but when he saw how crippled we were he refused to pay the six hundred dollars reward offered for us both, and told Sheriff Hunter to keep us in the jail until James came back. We were well treated while there, which was about twenty-eight days, and during that time my thoughts were directed to Him whom I never knew before. I felt that without His help I would never be free, and I prayed to my Great Father above to be with me in this time of trouble, and in His wisdom I relied. I felt a consciousness of His near presence and it seemed as though some unseen power personally addressed me.

It was impossible to escape from the cell we were confined in. As before stated it was the one in which condemned murderers and those convicted of the most heinous offences were incarcerated. It was very strong and constantly guarded; but Providence seemed to be helping us, for after being in it for about ten days Banks was taken very ill with malarial fever, owing a good deal to the damp walls, and we were removed to a roomier and pleasanter cell up-stairs. It had two windows, one of which faced the jailor’s house, and the other was on the opposite side. We had more light than in the dungeon, and altogether it was a vast improvement for us. Nothing could arouse me, however, from the despondent feeling, which weighed me down like a heavy cloud. Promptly as the sun arose I would greet him with a good morning, and as he sank in the west in all his scarlet splendor I would say farewell, hoping I would not live to see him again,

for I longed to die and be out of a world that stifled all of my best feelings, and in which on every side I met with only curses and blows.

Shortly after being put in this upper cell I commenced to look around for a means of escape. I pulled off one of the legs of a stove that was stored in a corner of our room, and with this I pried off a board on the side of our cell and found a small strip of iron about a foot long in one corner, which I managed to rip off, and then I put back the board so that everything would look undisturbed. With this iron strip I worked unceasingly on the east window, when I could do so unobserved, but all my efforts seemed in vain; it was too strong for me. The last day we were to be in our prison had come. It was Thursday. How well do I remember it and the sinking feeling that oppressed my heart when the jailor informed us that our master, Dr. James, had returned from Georgia and was now in Fredericksburg, expecting to be at the jail next morning. All hope seemed to leave me and I fully expected to spend my future days in slavery. After a while I grew more composed over the bad news of master’s return, and repeated with a calm sort of desperation that I would rather die than see the man that bought me. I then prayed to God that if I was to be captured again not to let me escape out of there, but if I could get away for Him to show me in His wisdom what to do. I had prayed both night and day up to this time and now began to think God had given me up. I got up and walked to the window, saying: “Window, I will never try you again unless in God’s name I am told to do so.” I turned away and started right across the floor to the opposite side to try and break the other window open. I knew it was the last day I had any chance and I felt desperate. Just at that moment I heard a voice say distinctly to me: “Go back to the window you have left. Since you have declared to do what is ordered in My name I will be with you.” I stood still and dared not move either back or forward. The mysterious voice was still ringing in my ears and I felt as one dazed; I feared to go back until my mind became impressed with the idea that it really was

the voice of the Great Master I had heard. He had taken pity on me in my extremity and would now help me. Something seemed to say, “Whose name did you invoke?” and I cried aloud, “God’s name.” I then went right back to the window and an unseen power directed me just what to do. Remember, I had been at work at this window for many weary days and nights and only a few minutes previously had exerted all my strength to burst it open, but in vain. Now, after leaving it and then coming back again in obedience to the mysterious mandate, I was not five minutes in splitting the bottom sill, in which the grates were fastened. While taking out the sash I accidentally broke two of the panes of glass, and this I felt would betray me and lead to discovery of our plans. Now that I knew that all things were ready for us to escape at night this one accident spoiled it all. The guard had to come in twice before nightfall and see if everything was right, and I felt he could not help but notice the broken panes. I put in the sash, broke off the fragment of glass left, put all the pieces in the stove, and listened for the footfall of our jailor. Our fate hung on a very slender thread, for if he saw anything was wrong all was lost, and as the broken glass was so plain before him it seemed almost impossible not to perceive it. At last a heavy tramp was heard and I tried to hold my breath as he came in. How eagerly we both noticed his every movement. The door grated harshly on the rusty hinges and he entered quickly, giving us a searching glance. Then, seeing we were quietly resting, he passed on and deliberately walked up to the broken window and looked out. We thought we were lost, but no; God seemed to blind his mind, and though he saw with his eyes he did not realize that anything was amiss; and finally, after looking for several moments turned unconcernedly on his heel and left us. Then I fell on my knees and said, “Surely, Lord, Thou art with us,” and something seemed to murmur in reply, “all will yet be well.” But we had still another ordeal to go through, for after supper he would return to see if everything was safe for the night. The minutes were like hours. Our fate seemed to hang on the turn of a die, and we ardently longed for

the moments to fly quicker. “Hope deferred truly maketh the heart sick,” and I fairly yearned to be out in the fresh air once more. Would the long, long day never go by, dragging along slowly, so slowly? We heard the heavy metalic pendulum with its steady tick, and from time to time the clock would sonorously strike the hour. I prayed that God would blind the jailor’s eyes and mind as before, so that he would not see or realize what had been done. Thus silently and prayerfully we awaited his coming. The slanting rays of the sun told us that night was coming on and soon her dark mantle began to fold around our prison home. Under her friendly veil we would make one last desperate effort to free ourselves again. At last the tread of our jailor was heard, and for a moment I wished the earth would open and swallow me, so fearful had I become of discovery. I, who knew not the meaning of nerves, felt completely unstrung, and I quivered and shook with fear. Banks lay close by me, and I said to him: “Remember Daniel was saved even when in the lion’s den, and we will yet be saved from these human tigers.” As if to verify what I had said, the guard gave but a casual glance around, staid only a few moments, and left. To paint the relief we felt were impossible. I clasped Banks and he me, and looking into each other’s eyes we both breathed one mighty prayer of thankfulnes to the great overruling power that we felt had saved us.

He also states regarding their religious beliefs as slaves the below:

The worthy ministers who performed the services were pretty actively employed in the obituary line of business, at this time, but they were fully equal to the occasion and had great command of language. Many of them could not read or write, but they would express themselves in their own peculiar phraseology, and, as they burned with a fiery zeal, it made up for defects of education. Taking into consideration the uncultured state of their hearers, these worthy men gave good satisfaction. Having great powers of imagery and felicity of expression, they would often astonish their educated white hearers, by the fluent, eloquent language used, and the many quaint expressions and original

interpretations of Scripture made by these earnest souls often showed a vein of thought of a high order.

We had our regular Wednesday night prayer meetings at each other’s houses, but they were held at the discretion of our master, and if the edict went forth that we could have none, we were obliged to hold them by stealth, like the Covenanters of old in Scotland. If we had a local minister he would preside, otherwise we would manage among ourselves. There would seldom be silence in our meetings, waiting for each other to speak, as I am told there is often in a white man’s prayer meeting. We were always ready, that is the religious ones, to testify, and felt much better for doing so. Some of the ministers were not allowed to preach if the master was arbitrary or down on them for something, as was frequently the case

And also

three days and then when I said farewell, he replied: “You will never see me any more on earth; let us try and meet above.”

I have often seen Africans not long out who could not speak English. They were chiefly Zulus, and were tatooed across the chest with stars. After a time they would begin to pick up some of our language, and then they would want us to be friendly and social with them. I remember them using these words, “You dem all come over and visit we dem all and we uns will go over and see you uns.” I heard of some that believed in voodouism and fetishism, but never saw any of their religious rites performed, though I believe that further south they practiced many superstitious observances.

End

Slavery (17th century – 1865)

The first people of Nigerian ancestry in what is now the modern United States were imported as slaves or indentured laborers from the 17th century onwards.[3] Calabar, Nigeria, became a major point of export of slaves from Africa to the Americas during the 17 and 18th centuries. Most slave ships frequenting this port were English.[4] Most of the slaves of Bight of Biafra – many of whom hailed from the Igbo hinterland – were imported to Virginia (which accounted for 60% of the Biafra´s slaves imported to United States, as well most of all slaves of Virginia) and South Carolina (arriving there the 34% of the Biafra´s slaves), surpassing in together the 30.000 slaves hailing from the Bight. These colonies were followed fundamentally by Maryland (where arrived the 4% of the Biafra´s slaves imported to United States, arriving more of 1,000 people of the Bight).[citation needed]

Under conditions in the European colonies, most English masters were not interested in the tribal origins, and often did not bother to record them at all, or if they did, accurately. After two and three centuries of residence in the United States and the lack of documentation because of enslavement, African Americans have often been unable to track their ancestors to specific ethnic groups or regions of Africa. More to the point, like other Americans, they have become a mixture of many different ancestries. Most slaves who came from Nigeria were likely to have been Igbo,[5] Yoruba, and Hausa. Other ethnic groups, such as the Fulani and Edo people were also captured and transported to the colonies in the New World. The Igbo were exported mainly to Maryland[6] and Virginia.[7] They comprised the majority of all slaves in Virginia during the 18th century: of the 37,000 African slaves imported to Virginia from Calabar during the eighteenth century, 30,000 were Igbo. In the next century, people of Igbo descent were taken with settlers who moved to Kentucky. According to some historians, the Igbo also comprised most of the slaves in Maryland,[7] although other sources say that most there were from Gambia.[citation needed]This group was characterized by rebellion and its high rate of suicide, as the people resisted the slavery to which they were subjected.

Some Nigerian ethnic groups, such as the Yoruba, and some northern Nigerian ethnic groups, had tribal facial identification marks. These could have assisted a returning slave in relocating his or her ethnic group, but few slaves escaped the colonies. In the colonies, masters tried to dissuade the practice of tribal customs. They also sometimes mixed people of different ethnic groups to make it more difficult for them to communicate and band together in rebellion.[8]

Missionaries when they came to Nigeria were dumbfounded to discover when they came to evangelize the Igbo People that the Igbo’s practiced many Hebraic/Jewish customs which they could not have learned from anyone else, it had to come from ancient practice of their people from antiquity; for they had no Bibles and met no one with a Bible until the missionaries came along.

They found that the Igbo’s practiced:

- Eating of animals that meet the Biblically clean requirements as well as the complete draining of blood from the animal as well as other laws concerning Kashrut

- The use of ritual washings like unto the mikvah

- Washing of Hand before and after meals

- Has a concept of clean and unclean, acceptable and abominable or taboo

- Animal sacrifice like unto the Levitical sacrificial system

- Believe in a Supreme, All-Powerful Deity (Chukwu) above all other deities

- Circumcision on the 8th day as well as had the naming ceremony of the 8 day old child

- Giving names that bear the name or title of G-d within it

- Separation of menstruating women

- Adah or Ada the name of the second woman mentioned in the Bible after Eve/Chavah (Gen. 4:19-20) and is also the title used to address the first born daughters of Igbo families

- The keeping a lunar calendar

- Shemita and Jubilee years: The annulment of debt and servitude every seven and fifty years

- The concept of a lifetime servant (Odibo) – Deut. 15:12-14, Ex. 21:2-6

- Burying their dead facing East, the direction of Jerusalem and the Promised Land

- Burying their dead as quickly as possible

- Sitting Shiva (seven day mourning period where one sits on low stools, remains unkempt and shave their head in grief)

- Belief in a resurrection

- Send the body’s home of Igbos who die outside of Igboland to be buried, like Joseph and Jacob desiring not to be buried in a pagan or foreign land

- Lengthy funeral ceremonies such as found in Gen. 50:1-3

- Preference of Inheritance and leadership was given to the first born and passed down through the fathers

- Sung prior to and carried a type of Ark into battle when they went to war

- Hospitality like unto the traditions and legends know of Abraham Offering water, meal and lodging to travelers

- The Yam Festival is like unto Shavuot (Feast of Weeks) and the Ovala Festival in the fall is like unto Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacles)

- Conversation and deliberate among men and leaders like that of Rabbi’s and students in a Yeshiva

- Levirate type marriages, brothers marrying deceased brothers wives to carry on the brothers name

- Marriage negotiations (Onye-aka-ebe) between families, like unto the story of Isaac and Rebecca

- Polygamy

- A type of, “Cities of Refuge,” where an Igbo who has committed a crime can seek refuge in his mother’s natal home, known in Igbo as, “Ikunne”

- The concept of Sanctuary, similar to the Igbo Osu caste concept where a victim of violence may flee to the altar (alusi) for divine protection (I Kings 2:28-30)

- Shunning of those who willingly break Igbo laws

- Shunning of those who marry outside of the Igbo people

- Laws against sexual perversion, incest and the like, they had to marry among their people but outside their immediate tribal clan

- Justice and punishment for certain crimes followed the lines of, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth”

- A rule of Torah (Law) was developed and was passed down by Eri

- No jails or penal system

- Rite of passage into adulthood

- Governance of the people by a conglomerate of tribal elders and judges prior to the institution of kingship dynasties

- The coronation of the Kings have rituals and customs that closely remember that of the coronation of Kings of Judah and Israel

- Symbolic attire and accessories of the Kings and Elders closely resembled that of Kings and Tribal leaders of Judah and Israel

- Igbo idioms are very much like, and carry similar meanings as Solomon’s book of Proverbs

These among many other Jewish laws and customs that we will get into great depth here shortly were found to be kept by the Igbo people and sadly, the Christian missionaries forced them to abandon many of these Hebraic practices because though they resembled Biblical worship of G-d, they believed many have been done away with due to the advent of Messiah and they believed they practiced these customs unto pagan gods and as such should be abandoned. The Igbo’s are slowly beginning to return to the pre-missionary practices, desiring to return to their Hebraic roots.

One Igbo man named Avraham, a Cantor of the Natsari Jewish community in Nigeria said,

“In a nutshell, every law as stated in the Torah was being practiced by our forefathers before the advent of Christianity. Except that our fathers went into idol worship, but they still kept the tradition as was handed over to them by their forefathers.”

Read the full story http://www.hebrewigbo.com/cultural.html

The deaf and dumb (as they put it) Hebrew African was described as AS BLACK AS THE ACE OF SPADES

See this runaway slave register where some of the slaves still have their African names in Jamaica.

Jamaica Runaway Slaves: 19th Century

Read From-Babylon-To-Timbuktu-by-Rudolph-R-Windsor

A list of other posts in this blog and some relevant posts.

links to all Black History posts in this blog.

The History of Ouidah aka Juda, Judea Judah Whydah

The Maroons: Africans who escaped from their captors